Diversity ∝ Leadership

Diversity and Inclusion departments work extremely hard on equitable and balanced hiring, a highly perused process today. There is diversity of gender, ethnicity, language, pedigree, and perspective.

A corporation’s goal-as a profit-maximising entity- is not simply to have ‘check-the box’ diversity, but to utilise ir in order to become better. Multiple perspectives nearly always create a stronger organisation with clearer objectives – set from the top.

Lee Kuan Yew decided decades ago to attract the best and brightest from around the world to make Singapore a global player. He was unconcerned about where they came from, but tremendously concerned that they were the best, and could truly contribute to Singapore’s development – whether botanists, academicians, bankers, aerospace or engineers. Indeed, Singapore has attracted a wide array of talent over the years, and today one can easily see Lee’s meritocratic imprint of Singapore’s success and its multiculturalism.

It is not much different at any corporation. Successful diversity and inclusion cannot emanate from a department, any more than successful hiring can be done by internal recruiters.

It is up to the CEO and top management to set the pace, drive the cultural change, and know exactly what and whom they want within their organisation.

Anything less than the CEO putting her imprimatur on talent and diversity is sub-optimal and inefficient.

Here is one [commercial] example which I think nicely encapsulates this point:

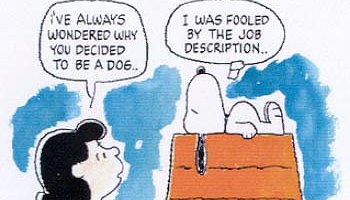

In his recent book, The Hard Things about Hard Things, Ben Horowitz recalls hiring a new head of sales. After interviewing twelve people, he met Mark Cranney, and after drilling him extensively thought was perfect for the job. Cranney had some difficulty communicating, but showed in great detail exactly how he had previously designed a winning sales team, and answered all questions perfectly. Horowitz knew Cranney was exactly what he needed at that particular point. But everyone else who interviewed Cranney disagreed, including his board.

Why?

He didn’t quite look the part of a senior sales person (wasn’t tall or slender enough), made some of the interviewers uncomfortable with his intensity, and didn’t come from a school anyone knew (Southern Utah). Cranney gave Horowitz–I can’t believe this, but it’s in the book– seventy five references. Horowitz apparently called them, and they all checked out very well. As he was about to make Cranney an offer, someone on his team said a friend of hers wanted to give a negative review.

I’ll let Horowitz tell the rest of it:

“I called the friend–I’ll call him Joe–and proceeded to have the most unusual reference call of my career:

Ben: “Thanks very much for reaching out.”

Joe: “My pleasure.”

Ben: “How do you know about Mark Cranney?”

Joe: “Mark was an area Vice President when I taught sales training at my previous employer. I want to tell you that under no circumstances should you hire him.”

Ben: “Wow, that’s a strong statement. Is he a criminal?”

Joe: “No. I’ve never known Mark to do anything unethical.”

Ben: “Is he bad at hiring?”

Joe: “No. He brought in some of the best salespeople into the company.”

Ben: “Can he do big deals?”

Joe: “Yes, definitely. Mark did some of the largest deals we had.”

Ben: “Is he a bad manager?”

Joe: “No, he was very effective at running his team.”

Ben: “Well, then, why shouldn’t I hire him?”

Joe: “He’d be a terrible cultural fit.”

Ben: “Please explain.”

Joe: “Well, when I was teaching new-hire sales training at Parametric Technology Corporation, I brought in Mark as a guest speaker to fire up the troops. We had fifty new hires, and I had them all excited about selling, and enthusiastic about working for the company. Mark Cranney walks up to the podium, looks at this crowd of fresh recruits, and says, ‘I don’t give a f–k how well trained you are. If you don’t bring me five hundred thousand dollars a quarter, I’m putting a bullet in your head.”

Ben: “Thank you very much.”

Horowitz still had to convince the board. His company was ‘at war’ at that time, and needed a wartime general to ‘kill the enemy and get the troops home safely.’ He was soon able to hire Cranney.

“He wasn’t an easy cultural fit, but he was a genius. I needed his genius and worked with him on the fit. I don’t know that every member on the team ever became totally comfortable with Mark, but in the end they all agreed that he was the best person possible for the job.”*

By the way, I looked up Mark Cranney on LinkedIn to see for myself. He is a Partner at Andreessen Horowitz, so something clearly clicked, as they’ve worked together for years now.

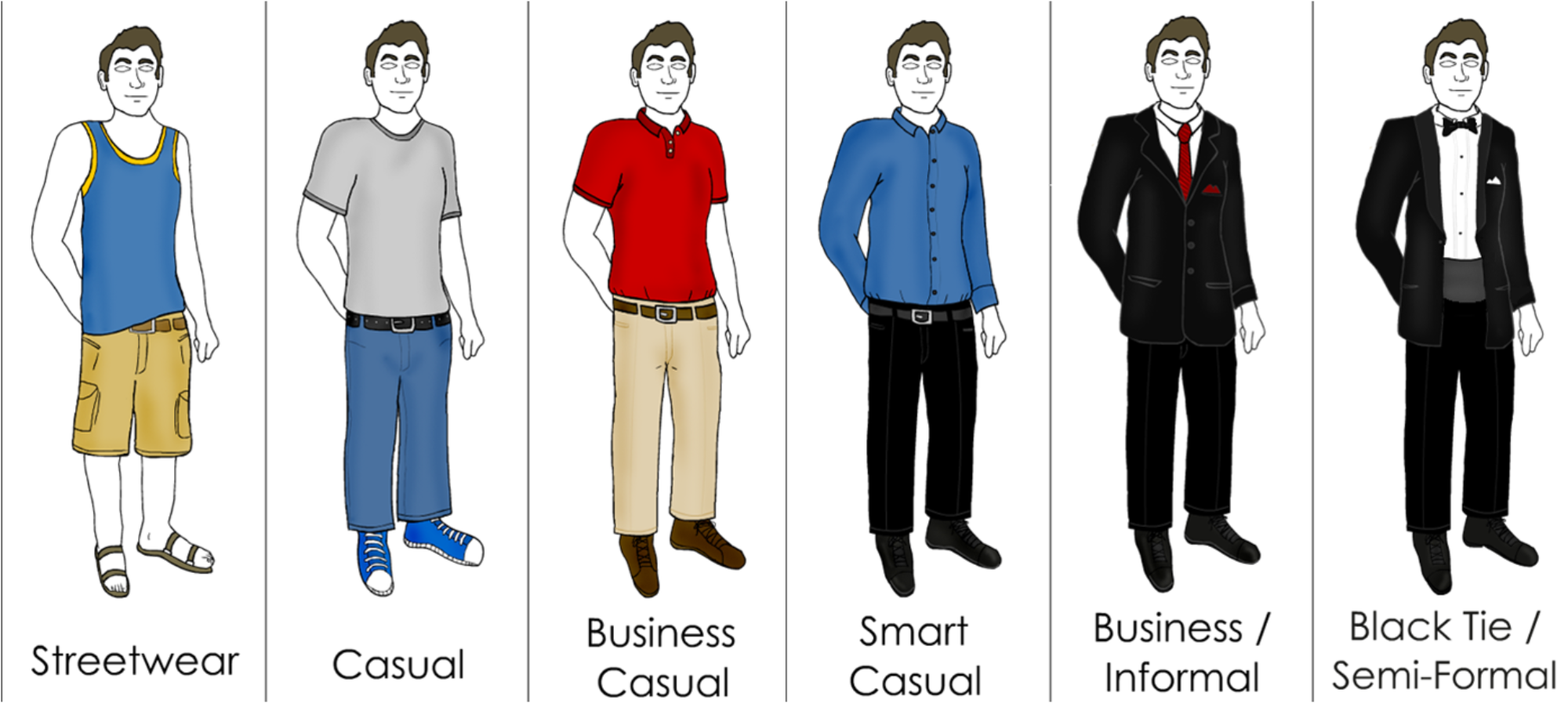

If you want diversity within an organisation-and you’re senior enough to make such decisions-know what you must have. Hire on profound strengths and manage idiosyncrasies. Skip over appearance, body language, pedigree or deportment [within reason, obviously].

‘If we do not attract, welcome and make foreign talent feel comfortable in Singapore, we will not be a global city and if we are not a global city, it doesn’t count for much. The days of being a regional city, that’s over.’

–LKY, 2003.

Whether a city-state or a company, the same rules apply.

–

*Harper Collins, pp 95-98