All in favour say “Ay”… uh-oh..

When senior management gathers around the meeting room table, the focus is often on decisions to be agreed upon, short-term or long-term, the impact on corporate performance and direction, all fairly standard stuff.

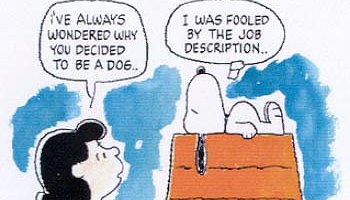

A decision is always a choice-usually between not-so-good and potentially good ones, hardly ever between a great and awful choice. No guarantees what will work, but everyone thinks they know the right choice.

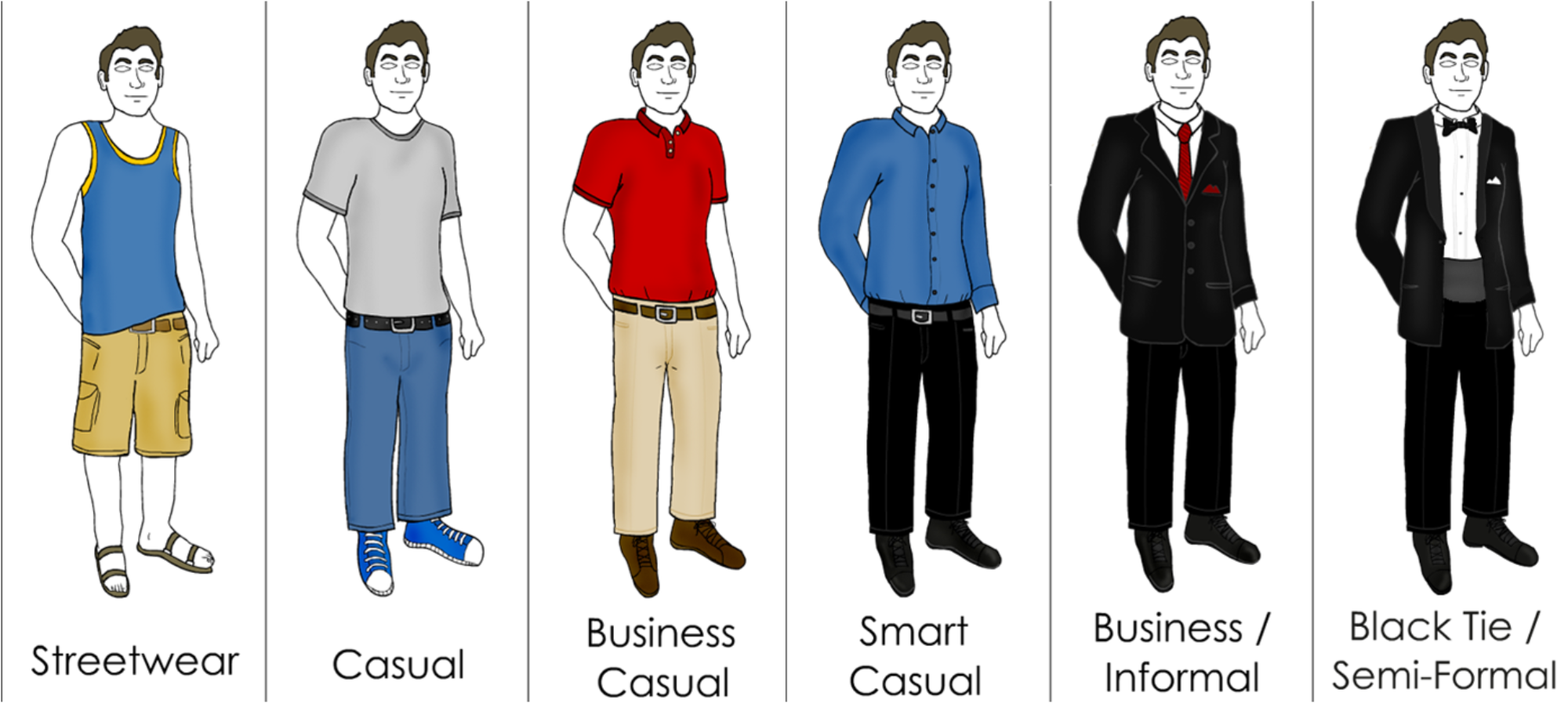

When the meeting convenes and collective decisions are to be made, the Chair/CEO/Pres, etc, kicks it off–the underlying dynamic often reverts back to the teacher’s universal classroom line “If no one has any questions, I all expect you to all get A’s on the test.” In the boardroom, it may be translated as:

“Here is how I see our (sales/revenue/R&D/talent/technology/output/investments/investors, etc) growing, and here is how we are going forth to achieve YYY. We’ve thought this through, and it makes damned good sense to all of us. Questions anyone? If not, let’s move on to the next subject, lots to cover.”

No one around that table wants to raise their hand and cross swords for fear of getting stabbed (which can happen). In boardrooms all over the world, when the question comes up on a significant decision (“All in favour please raise their hand or say ‘Ay'”), almost everyone does so–it is the sane thing to do–and the grumbling or pushback starts after the meeting is over, in the corridors, over a meal, on the phone or yes, email as well.

Making good business decisions is much like working in a lab; when investigating, one must have different hypotheses to test against, over and over to measure results–there is simply no other way to do effective R&D. No researcher would ever say: “This should work! I just know if we get enough extremely smart scientists together to work on it, we’ll soon figure it out and solve the problem, no doubt about it.”

How should a group decision be made for a significant investment? Get differing opinions. You cannot start a discussion with facts. People almost always start talking by expressing opinions, and back it up with facts to support the opinion–that’s the way the world pivots–always has.

The critical difference–and what leaders should always demand and look for–is to get well-reasoned opinions that can be backed up, not necessarily reflecting popular opinion. And if someone has worked in a business over 20 years, let’s say, they SHOULD have opinions based on experience. Companies hire senior people for their thinking, not their function..

How can a company have a “Plan B” or backup unless they have diverging thoughts among their top team? If everyone agrees, there’s no fall back. Look at any national government-there is (almost) always checks and balances. In the US, the State Dept, the NSC, DOD, consistently disagree on strategy.Is that good? Of course it is. Policy, and policy-making, is fluid, not static, and leaders (business or politics) are there to create policy, not to be functional administrators.

A difference of opinion is not the same thing as clashing over and over and having knock-down fights. Forcing smart and experienced people to think of alternatives, and come back to the next meeting with researched thoughts that may result in better organisational decisions is one easy step for leaders to up their company’s game a couple of notches.

So the next time the boss says “All in favour”, think a bit more carefully before shooting your hand up.