Cross-cultural cantatas and chorales

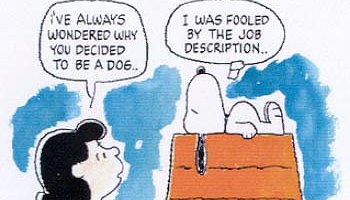

A client once got hold of me a few years ago to ask if I did coaching for communication. One of his ‘high-po’s’ in Tokyo was having difficulty communicating on conference calls. He asked if that was something I did.

I asked him whether it was her lack of English fluency, or knowing what to say but getting tongue-tied. He quickly replied that it was the latter; her spoken English was reasonably good, but on calls or vidoecons, she said little. Most of the management was American, some European and Indian, fewer Asians, and he’d received some polite jabs from them about her quiescence.

I did end up talking with her, and not surprisingly, she was completely unaware of their concerns. She was very clear to me when I asked about her rectitude; when there was something worth saying, she would speak out with no hesitation. If not, her time was best used by taking notes and listening carefully.

That is, of course, fundamentally different from the Western, more free-wheeling call or meeting . She liked her job, liked the company, and realised if she was going to stay and grow, her style would have to change–enough to be thought of as ‘one of them’, She learned how to verbally elbow her way in to a conversation (even if she didn’t have a strong point to make) but to make herself heard. She is still with them, by the way.

For all the talk of the global and culturally diverse MNC, there remains a yawning cross-cultural communicative lacuna.

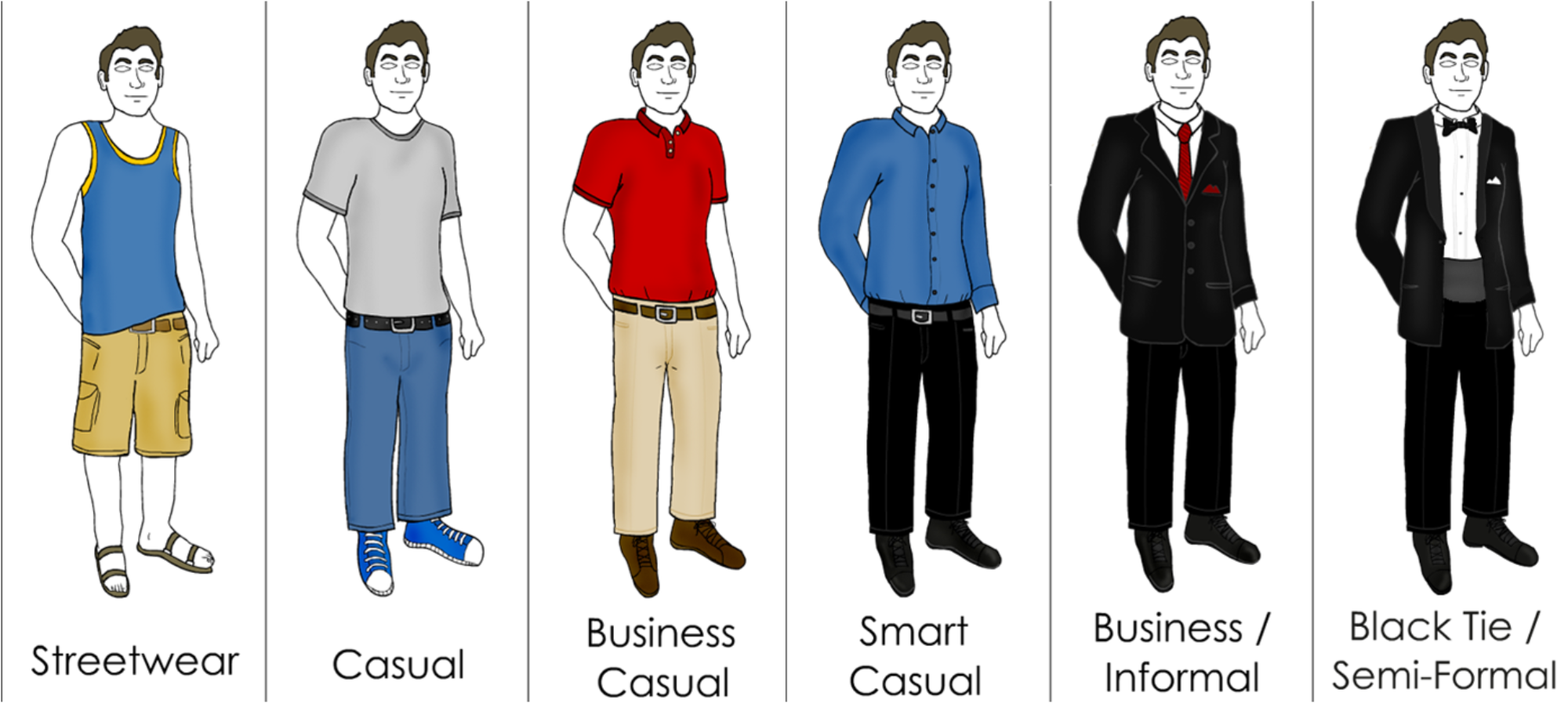

Here are some thoughts to consider for those engaging in business or hiring in Asia:

It’s often acceptable to say less, and make each word count.

Americans are notorious for filling the silence, not allowing a conversational lull. Many times when coaching, I’ve had long pauses, face to face or on the phone. I’m sorely tempted to jump in, but I bite my tongue until a reply is given. And I always get one.

Pico Iyer, in a book review of Natsume Soseki in the New York Review of Bookswrote:

“There are few emphases in spoken Japanese—the aim is to remain as level, even as neutral, and to present a surface that gives little away. It’s what’s not expressed that sits at the heart of a haiku.”

Japan is hardly Asia, but Iyer’s comment reflects how life truly is in the details, and to make a point with less rather than more.

Many Westerners forget how quickly they talk once out of their home country. Even for non-native speakers whose English is very good, listening to a rat-a-tat soliloquy is difficult. That doesn’t mean one should dumb down, but to scale it back a bit, enunciate a shade more, ease up on the slang and listen more than talk, Easy peasy..

Don’t get blinkered by those who DO speak outstanding English.

This might seem contradictory, but isn’t, especially when hiring. I recall one US client telling me she wanted to hire someone in Asia who “spoke unaccented English.” ‘Unaccented to whom?’ I thought. But not an unusual request. Clients have said, ‘I think this person is great, he/she speaks such good English. We really connected, and that’s what I need.’

English fluency is, without question, quite helpful for hiring in Asia. That’s one component, but does not equate with either having the right strategic thinking, nor fitting into the role and corporate culture. I can think of another large US FMCG company that made it a point of only hiring fluent English speaking Chinese for all their China hires. Their profit in China started to erode, and while I can’t say precisely how much was due to their visible tilt on English, I wouldn’t discount it.

I once coached a young mainland Chinese manager (I’ll call him Joe) for a US MNC. He had been given a large regional role, the coaching was to help him transition into his new job. He had not worked outside China, but had extremely good English. His direct boss was in the US, and they spoke weekly, if not more. His boss thought Joe knew and understood more than he did, in part because his English was so good, but Joe made some missteps which increasingly irritated his boss. Even with the coaching, he struggled to manage, and they decided to hire someone above him. He left the company soon after. Moral: English fluency is only one factor in an overseas hire. Both sides have to [ideally] meet in the middle.

Try not to put people on the spot.

We are not ‘In the pit with Jack’ anymore, but more likely trying to build bridges in various parts of the world. There is a time and place to solicit opinions, but shining a klieg light to force a reply will often result in a flaccid response, a loss of face not easily repaired. Many years ago in Hong Kong I worked for a European tyrant. I was In his office one day sorting out a problem and he called in one of the junior staff, sat him down and demanded an answer regarding the issue we were working on. I can still see the sweat puring down this young chaps face. He was mute, and the boss kept yelling at him to give an answer. He finally mumbled an incoherent reply, the tyrant yelled again, waved his hand and sent him out of the office. He was just trying to translate the words from Cantonese into English ( I know as I spoke to the staff afterwards) and had laboured mightily. An extreme case, admittedly, but the Socratic style of enquiry has not fully hatched in Asia. Know how to ask directly, but some deference is do-able, with practise and finesse.

Hesitancy is not necessarily a detriment.

I met a Western client who wanted one of his [Asian] managers to be less hesitant, to be ‘less loved and more feared’. Not respected; feared.

He was more a quiet consensus builder, and struggled to accommodate the cultural norms of his boss-and company-as they wanted a more confrontational style. It didn’t work very well. The boss had little patience, and the manager felt he was being bullied to treat his staff in a manner he didn’t think would produce results, and eventually left. His boss replaced him with a non Asian who had similar traits as the boss.

Hesitating, rather than acting, has its merits. As Eisenhower once said to Dulles, “Don’t just do something-stand there!”

It doesn’t mean one should ‘go local’ or try to change the corporate culture. It does mean that what works in one place doesn’t necessarily work elsewhere. Be flexible, as MNC’s cannot manage the same everywhere in the world. Impossible.

––

There are hundreds of paths up the mountain. Know where you are on that path, and know who’s in front and behind of you to navigate up to the top. Bring along your communicative repertoire to anticipate unexpected weather changes, a modicum of circumspection in the backpack to use as needed, and a walking stick that won’t easily snap in two.